Building a shed door should be kept simple, but how simple a construction should you use?

Building a shed door can be a simple task, do the basics right and you will feel proud every time you go in to your shed. The first part of this page shows you the types of shed door, the parts of the door and how they go together. I then show you how to build a shed door step by step, with pictures of a shed door that recently made.

Let's get started with the different types of door and which is best to build.

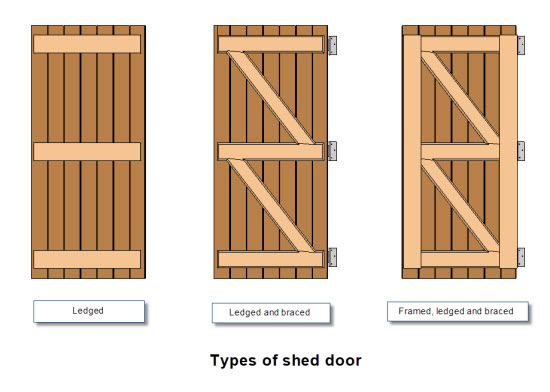

There are three levels of construction that you could opt for before deciding to go the whole hog and buy a ready-made door and frame.

These types of door are:

- Ledged

- Ledged and braced

- Framed, ledged and braced

A good balance of ease of construction can be achieved with the ledged and braced door

The simple ledged door has a tendency to drop over time. Due to expansion and contraction of the timber gravity takes a hold and eventually the door bolt won't line up with the keep on the frame.

The framed ledged and braced door is the strongest and most stable of the three. The door is prevented from dropping by the diagonal braces and the frame around the perimeter helps to make the door more secure and prevent warping of the whole door. However this does come at a cost of complexity. To make a good framed, ledged and braced door you will need to construct mortise and tenon joints for the frame and braces.

A happy medium of the two is the ledged and braced door. This is the one that I show in the step by step building a shed door instructions further down this page. The braces stop the door from dropping/sagging and the ledges provide a good opportunity to fix security bolts between the door and the frame.

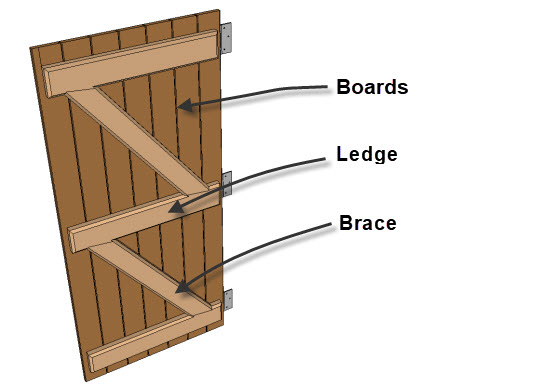

So what are the main components of a ledged and braced door?

The three main components are:

- Boards - These form the face of the door

- Ledges - These are the horizontal boards

- Braces - These are the diagonal boards

Elements of a shed door

Elements of a shed door

If you are building a shed door there is a wide degree of combinations of thickness and type of materials that can be used to construct each of these shed door components. But generally the thicker and better quality the timber the stronger and more stable the final result will be.

It goes without saying that many commercially built sheds are built with thin material and of fairly minimal construction. They all work initially but over time the lack of quality starts to show. As the door drops, the boards warp etc.

So what materials should you use to construct your shed door?

Let's start with the boards that form the main body of the door. These are often made from the same material as the rest of the shed cladding for economy (only one type of material to order) and visual continuity (the door matches the rest of the shed).

In the example below I departed from this convention to make a door that contrasted with the cladding of the shed. This contrast came with a time and cost penalty (though I was very happy with the result).

The simplest type of board to use is the interlocking tongue and groove type. As these boards interlock there is no gap between them for draughts. Tongue and groove boards start at about 12mm thick (very thin) and go up to around 20mm.

|

When buying timber (of any type) be aware of the difference between rough sawn and planed timber. Often suppliers will quote the rough sawn size (it is always larger) assuming that you know that the planed timber size will actually be smaller. This isn't a con trick or them being dis-honest it is just part of the process of taking timber from a tree to the finished log. However to the unititiated it can be confusing: For cladding size timber :

I prefer rough sawn timber for cladding sheds for three reasons:

|

As you will soon see I used 20mm thick, rough sawn, square edge boards and so needed a cover strip to weather proof the gaps between the boards. This was part of my design, but one that added a little extra to the time needed to make the door.

If you are building a shed door for the first time then I would recommend that you use tongue and groove boards.

Ledges and braces

If you are using 20mm thick boards for the face of the door then you could use the same timber for the ledges and braces. But if you are using that skinny 12mm thick planed material I would recommend that you use something thicker like 32x45 for the ledges and braces.

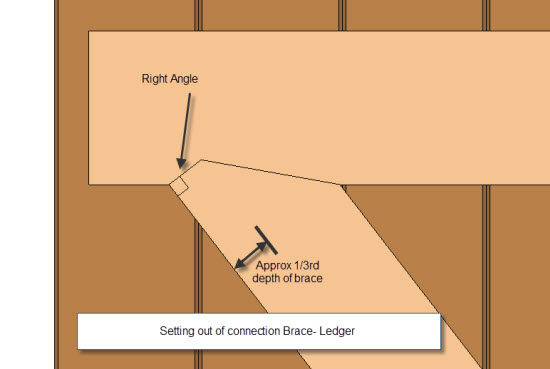

Connections between ledges and braces

There is no structural connection between the two. The traditional method is to make a notch in the ledger as in this sketch so that the brace is always in compression.

Setting out of the interface between a brace and ledge

Setting out of the interface between a brace and ledge

What connectors are used to connect the ledges and braces to the door?

Traditionally ledged and braced doors are nailed from the front. This works when fixing through thinner material into a thicker brace or ledge behind.

When fixing with nails like this then typically the nail lengh is 2.5 times the thickness of the door facing material.

For building a shed door like this you will see that I opted to use screws and use them from the inside of the door. This meant that the fixings are protected from the weather and the front of the door is not damaged. It also gives the front of the door a 'cleaner' appearance.

If you use a timber such as oak or sweet chestnut for building a shed door then you will also need to use Stainless Steel screws as they are resistant to the acidic tannins in these woods.

We have now covered the basics of building a shed door

So let's get on with building a shed door

I mentioned earlier that it would definitely save you time to buy ready cut boards, with a tongue and groove profile, but would it be as much fun?

The boards that I used here were 20mm thick, rough sawn, waney edge boards which are almost a waste product from the saw mill that I bought them from.

The boards as bought were 'wet' and needed time to air dry (allow approximately one year per inch of thickness). To keep the boards relatively straight, stack them with timber spacers every 3-400mm and keep a weight on top while they dry out.

Laying out and assessing the waney edge boards

Laying out and assessing the waney edge boards

Cutting the boards to width would normally be done on a table saw

For a small number of boards such as this it is slightly more time-consuming - but relatively straightforward - to use a standard hand held circular saw. Use a straight floor board as a straight edge for the first cut and then make use of the width guide which is part of the saw's add-ons to cut the opposite side.

When cutting the board you will need to use your own skill and judgement to cut off the sap wood while maximising the useful width of the board. It is also really helpful to inspect the timber and see what features you want to cut out or include.

You need to cut off the end checks and splits but there may be some interesting knot or grain features that you want to include.

The main priority in my view is to maximise the width of boards achieved.

Board clamped to bench and cutting off the waney edge

Board clamped to bench and cutting off the waney edge

Decide on the width and height of your door

The dimensions of the door for this shed were 600x1800mm. I cut the boards to length and laid them out to work out what I thought as the best arrangement.

Laying out the boards for the door

Laying out the boards for the door

When arranging the boards for building a shed door take into account the orientation of the growth rings. Due to the nature of the boards, the outside of the board will expand and shrink at a different rate to the inside, leading to an effect known as 'cupping'.

'Cupping' can be mitigated by fixing the heartwood on the outside so that the screws/fixings clamp the board to the batten keeping it as straight as possible.

Close up view of end grain. The board nearest the camera has the heartwood facing to the outside. The board

next to it is placed incorrectly with the heartwood facing inward and will be flipped over to minimise 'cupping'

Close up view of end grain. The board nearest the camera has the heartwood facing to the outside. The board

next to it is placed incorrectly with the heartwood facing inward and will be flipped over to minimise 'cupping'

Arrange the battens and braces on the back of the door

I used three boards across the back to form the ledges for this door. The ledges keep the face of the door straight and provide a connection between each of the boards. You will see that sometimes people attempt to reduce the number of ledges to two. This is a false economy in my view and makes the door less robust.

When building a shed door, the slope direction of the braces is important. Timber swells and contracts perpendicular to the grain but varies little dimensionally along the grain.

Having the braces sloping up from the bottom and middle hinge puts the brace into compression. This means that the weight of the door is trying to close the joint all the time and push the brace into the housing.

If the brace was the other way up then the weight of the door would be trying to open the joint, which given enough time along with wet and dry cycles, would happen. Then the door would no longer be square and start to sag.

Laying out the ledgers and braces on the back of the door

Laying out the ledgers and braces on the back of the door

|

Note: When you take a look at doors on commercial sheds you often see that they have one brace sloping up and one sloping downwards. I believe that this is to hedge their bets and so that they are guaranteed that at least one brace will be effective whichever way up the door is hung. |

Once you have decided on the arrangement for the ledges and the braces, mark these on the boards and cut out the housings. Using a chisel and mallet is the easiest method to do this.

Building a shed door - Cutting in the braces with a mallet and chisel

Building a shed door - Cutting in the braces with a mallet and chisel

A final touch for the ledges and braces is to plane (or use a router) to add a small chamfer to each of the exposed edges. This increases the visual appeal of the elements and also reduces the possibility of splinters and splitting of the edges.

Fixing the door together

Use clamps to pull the boards together and also to hold the ledges and braces in position while you fix them in place. The traditional method of fixing the battens to the door was to nail from the 'front' of the door through the board and ledger.

The end of the nail was then 'clenched' which means bashing the end of the nail over so that the nail couldn't be removed. With the advent of modern fixings I choose to secure the battens and braces from the back of the door with screws, thereby giving the front of the door a less cluttered look.

Close up of brace and fixings. Note that holes for screws are pre-drilled and countersunk

Close up of brace and fixings. Note that holes for screws are pre-drilled and countersunk

Remember to use stainless steel screws when working with sweet chestnut or oak. The natural tannins within the wood, which are responsible for the timber's durability, are acidic and promote corrosion in plain steel fixings.

Moreover,sweet chestnut can be prone to splitting when relatively unseasoned so pre-drilling and countersinking the screw holes reduces the possibility of this happening.

Fixing the shed door hinges

Make sure you understand where the hinge pin sits in relation to the door opening so that you fit the hinge in the correct position. This will prevent problems further down the line when you come to hang the door.

Fitting the hinges

Fitting the hinges

Fitting the cover strips

If you are building a shed door out of the more commonly available tongue and groove boarding then you can omit this step.

Making a door from plain edge board means that gaps will appear between the boards dependent on the season of the year and the moisture content of the door. The cover strips that we added are to keep out the worst of the rain and wind. Though having a tongue and groove board or a loose tongue rebated between the boards is definitely an alternative solution.

Fitting the cover strips

Fitting the cover strips

I liked the appearance of the cover strips especially after seeing something similar on a visit to my local pub ;-).

Pub door of similar construction with cover strips

Pub door of similar construction with cover strips

Finishing the door

With the door complete, apply a couple of coats of linseed oil or teak oil. These treatments soak into the fabric of the timber and add to its natural durability. They also make it easier to recoat and maintain as unlike paint they repel water and moisture does not get trapped behind them.

Completed door with coat of linseed oil

Completed door with coat of linseed oil

You will of course need some door furniture, a lock and/or a handle to secure the door. The best fittings that I have come across are the 'long throw' style locks.

These fittings use a Euro-style cylinder and have a 20mm square stainless steel bolt with a metal housing that has sufficient tolerance to accommodate the sort of timber movement to be expected on a shed.

I chose to make a simple slide bolt out of timber for everyday opening and closing, with a more secure bolt for when the shed has contents that are to be left unattended.

Find out more about the different types of shed door latch here

Simple timber slide bolt

Simple timber slide bolt

Related posts:

- How to hang the shed door that you have just built

- How to straighten a sagging shed door

- What type of hinges will you use on your ledged and braced shed door?

- How to construct a really strong shed door

Keep in touch with our monthly newsletter

Shed Building Monthly